Given the deadlock in the US congress on the question of funding for Ukraine, in the context of weakening support in Europe for a war now in its third year, and with witness to recent significant gains of territory by Russia, the past few weeks have seen a frenzy of discussion about creative (and uncreative) ways for Ukraine’s allies to fund the war effort.

This is money/power, on the grandest and gravest stage.

There are currently two main options on the table: the first is ill-conceived (or at least wrongly conceptualized), while the latter is quite fascinating. Highlighting the vast differences between these two approaches helps to clarify what is at stake in the question of funding Ukraine’s war efforts, and it reveals a great deal about how money relations actually work with and through power relations.

Seize the Cash

The position for which it is easiest to write an op-ed grounded on indignation and moral outrage is a simple one, and has recently been advanced by none other than Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission. The Central Bank of Russia (CBR) holds approximately $300 billion1 in reserves on deposit at the central banks and clearinghouse banks of Ukrainian allies. At this moment, when funds for Ukraine appear scarce and getting scarcer, the argument seems easy: “seize” that $300 billion and give it to Ukraine.

This idea was previously mooted, but largely ignored, at the start of the war. But as a political solution now, the notion proves even more enticing, because from the perspective of its western allies this seems like a way to give Ukraine money, without having to give them our money. How perfect would it be to just give them Russia’s money? Win, win.

To illustrate the idea,2 here’s a recent Bloomberg opinion piece arguing that international law can and should be used to justify the confiscation of Russian money:

The immediate question is whether countries that hold currency reserves owned by the Russian central bank may legally confiscate that money and give it to Ukraine as war reparations. … So far, scholars, politicians and pundits — including me — have been coy about transferring the Kremlin’s sovereign cash to Kyiv.

Wait, what? Transfer the Kremlin’s cash? Sovereign cash? I’m taking the question of the nature of money seriously, and not being pedantic, when I ask, “what does that even mean?”

The phrase transfer the cash evokes images of bags full of paper currency notes that we would send to Ukraine. For many readers it might call to mind the duffel bags stuffed with US dollars that the US military and private defense contractors physically carried to Iraq between 2003 and 2011. Those US $100 bills were, in fact, “sovereign cash.” But sovereign cash is the liability of the sovereign; in this case, what the US Federal Reserve owes to the physical holder of the bill.

Russia’s “sovereign cash” would be CBR issued paper currency, e.g. ₽100 notes. We can quickly see the myriad problems with this conception:

Western central banks don’t have bags of rubles in their vaults.

Even if they did, sending those bags to Kyiv would not provide Ukraine with any funding, because Russia is not going to honor its debt in the form of credits held by its enemy.

The conception is backwards from the start: “sovereign cash” is the liability of the CBR, but the CBR’s deposit accounts at the Fed (or ECB) are CBR assets and Fed liabilities.

Before we can even begin to solve the problem of funding Ukraine, we have to get clear on the nature of Russia’s “foreign assets.” Their money assets take the form of CBR deposit accounts held at western (usually central) banks, and these are quite different from their non-money assets. Those who choose the “seize the assets” option continually conflate the two.

For example, Bloomberg writes about specific discussions in the UK:

Officials from several UK government departments are studying plans to seize assets ranging from property owned by oligarchs to money in their bank accounts. But the focus of most attention is Russia’s central bank.

No. Those two bolded entities are not the same.

The case of property is easy: the UK government would direct local councils to auction off the houses and estates of Russian oligarchs, re-title the property in the name of the auction winner, and then hand over the proceeds of the auction sale to the UK government, which can then pass that money along to Ukraine.3 Note that the money Ukraine eventually gets comes directly from the house buyer. The house is a positive non-money asset owned by the Russians. The UK state seizes that asset and then turns it into a money-claim (first, on a commercial UK bank, then, on the BoE4) by selling it to the home-buyer.

The basic idea that animates this strategy to fund Ukraine is simply to “seize the money” the same way we might seize a house, or a yacht.

But money doesn’t work like that.

The idea of seizing Russian money emerged when Russia first invaded Ukraine. I addressed it in my book, vis-a-vis the putative $100 billion in CBR deposits at the fed. I wrote:

prior to the start of the war, the Fed’s balance sheet included a line on its liability column, as follows: “$100 billion deposit – CBR.” The $100 billion in question is the Fed’s debt; it is nothing more or less than what the Fed owes to the CBR. The sanctions against Russia manifest in the Fed refusing to honor that debt – that is, intentionally defaulting and therefore rejecting any Russian attempts to transfer that debt to someone else. Concretely, if Russia tries to spend their Fed deposits [their] check will bounce.

Crucially, however, because Russia’s deposits at the Fed take the form of debt for the Fed, there is absolutely nothing to seize, liquidate, distribute, or otherwise give to Ukraine. Before the war started, the Fed listed the $100 billion CBR deposit as a liability; after the invasion when sanctions are imposed, the Fed draws a line through that debt. The Fed was not holding gold bars for Russia, so it cannot confiscate those bars and send them to Ukraine

The only way in which the concept of “seizing money” can be rendered intelligible is in a case involving three distinct parties: the creditor, the debtor, and the seizer. This is the core money-structure of every bank heist movie. A commercial bank holds a bunch of physical paper notes in its vault. Paper currency, to reiterate, is a claim on the central bank, as debtor, with whoever holds it (here the commercial bank) being the creditor. Bank robbers then break into the vault and make off with the cash. Stealing cash makes you the creditor because you now hold the token of debt.

If we want to get really creative, we could also spin a story in which a debtor steals back their own token from the creditor. This would be a really bad J.J. Abrams movie, wherein the CIA and MI6 break into the vaults of banks in Russia and steal duffel bag after duffel bag filled with pound notes and dollar bills (that the Russian banks, for some strange reason, held as international reserves in the form of paper currency).5

Thus, there are rare and odd ways in which one might “seize” – almost always in the form of stealing – paper currency. But this is not the form that Russian money takes today. If Russia had crates filled with untraceable US dollar bills and Euro notes, nothing would stop them from spending them. These would be circulating claims on the Fed and the ECB, but there would be nothing for Ukraine’s allies to discuss in terms of policy choices. Those notes and bills could never help fund Ukraine’s war effort, because they would already be funding Russia’s.

Instead, Russia’s money takes the form of deposit accounts at the Fed and ECB. These too are liabilities of the Fed and ECB, but they illuminate my overall point.

You cannot seize a bank deposit, you can only freeze it.

When police arrest and indict both drug dealers and bank robbers, they seize the cash (and the drugs, and the guns!) in just the way I described above.6 But they freeze the bank accounts. The indicted criminals cannot transfer their money claims on commercial banks, in order to pay for things like lawyers, or private flights to flee. And the criminal proceedings may even reach a point at which the courts transfer the deposit to another creditor (perhaps the state). But we must be clear about what happens here: it’s the court that instructs the bank to both recognize the debt and change the identity of the creditor (transfer it to them). That’s not “seizing” anything.

In cases of criminal activity it’s often the case the bank deposits are themselves the ill-gotten gains of crime, and further, in an even smaller subset of cases, authorities may be able to identify the victim. In cases like these the remedy is obvious and straightforward: courts instruct the bank to transfer the deposit from the criminal’s account to an account in the name of the victim. If I scam you by having you wire money into my account, and the police catch me, they will tell my bank to write you a check or open an account in your name – funding this move by draining my deposit account.7

A bank deposit is money-credit. The digits in the bank ledger (which show up on the ATM screen or in your phone banking app) are themselves the tokens symbolizing the liability of the bank and the asset of the depositor. But the deposits, like all money-credits, always represent a claim on future value. There is no substantive value there “in” the account. All a money holder ever has is their claim on a debtor. When it comes to money, value is always only future value.

In a sense, then, your money in the bank does not manifest as “real” until the moment you spend it – until the precise point at which you transfer your claim on your bank to the person you are paying. The bank can honor that transfer or not (the transfer can thus succeed or fail), but they cannot take anything from you – they owe you. Similarly, the BoE, ECB, Fed, etc. all owe the CBR money. They can freeze CBR accounts or even cancel the CBR’s credit, but none of that generates new money-credits because it does not generate a new valid claim on future value.

Sell a bond

In reality, Ukraine does not actually need any money right now. They need weapons. Following first principles, nothing prevents Ukraine’s allies from manufacturing weaponry and shipping it to Ukraine. Of course, we are not following first principles here. We are following capitalist principles, and the rules of capitalism dictate that goods can only be handed over in exchange for money-credits.

This means that Ukraine’s allies must first give or loan Ukraine money, so that Ukraine can then hand that money back in exchange for the weapons it needs. The first step is largely superfluous or ceremonial: Ukraine needs its allies to send weapons on credit; Kyiv needs to “run a tab” with the west, to owe them. The solution everyone is searching for is this: how to create a new, viable debt for Ukraine (i.e., a condition in which its allies are owed money from Ukraine).

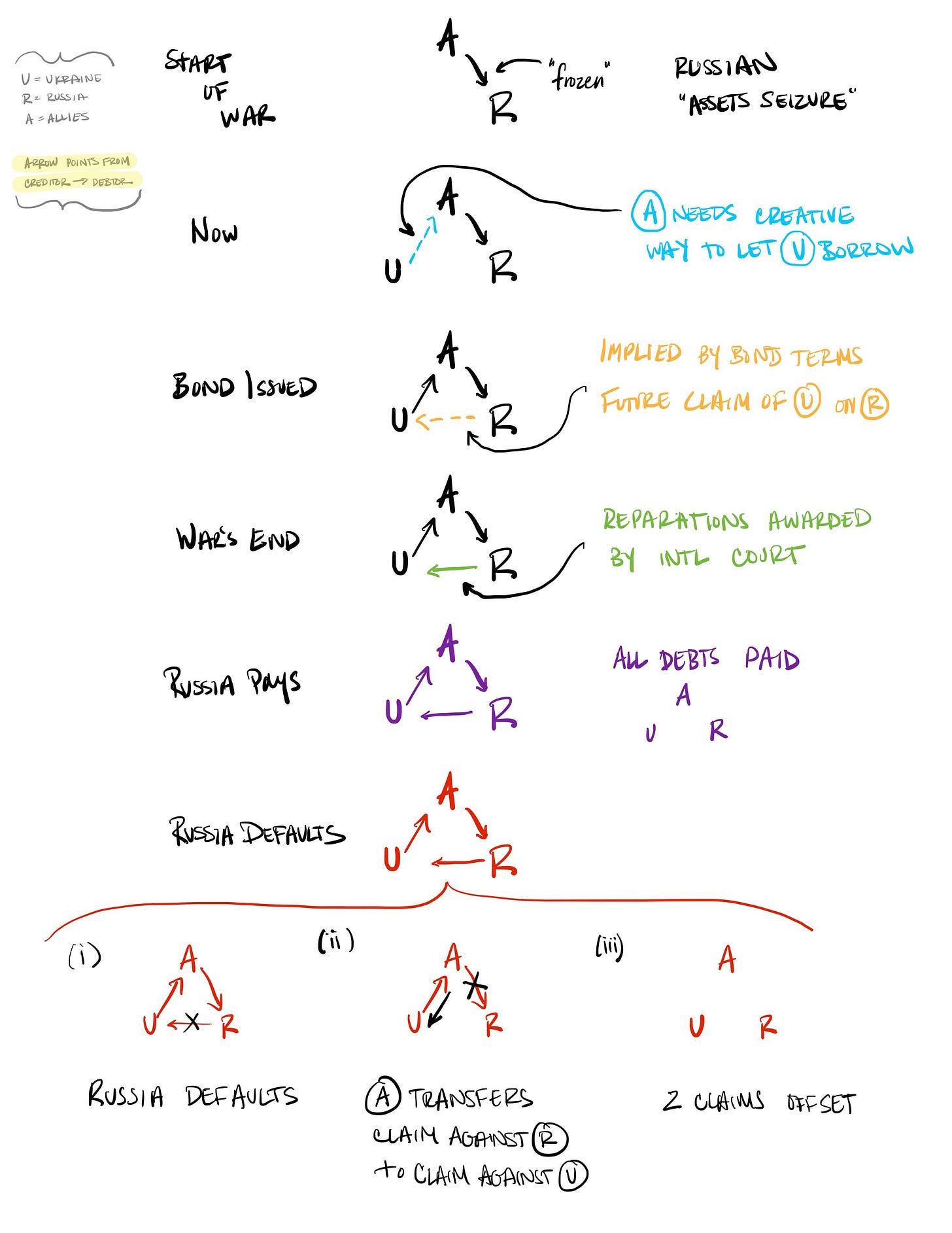

But the posited invalidity of Russia’s claim on its debtors (the US and Europe) does not create a valid claim for Ukraine on those same parties. At the first level, the two have nothing to do with one another. Currently, Ukraine’s allies (a) owe a debt to Russia, and (b) would like to have Ukraine owe them a debt (by loaning Ukraine money), but at present these credit/debt relations have no connection to one another. [see Start of War and Now in Figure 1, below]

The magic of financial engineering is to connect them. In other words, we need a financial product that will somehow transform Russia’s invalid claim on its G7 debtors into Ukraine’s valid claim on same. To do this, we will need to form a link – a money link – between Ukraine and Russia.

Here’s that Bloomberg piece again, making a hard pivot in the very same paragraph I quoted above:

An alternative proposal to seizing the assets is to issue bonds, using the funds as collateral, which has also been discussed.

I have already shown that seizing assets is simple but conceptually incoherent. Issuing a bond is the inverse – both coherent and complex.

To explain how it works,8 we start with some basic background: a “loan” and a “bond” are fundamentally the same thing, but they can have radically different connotations. For a loan, the borrower borrows money that it will have to pay back. For a bond, the issuer sells the bond as a financial asset. The asset is thought to have value in the present because of the projected future cash flows that the issuer is projected to generate. We usually think of a borrower as in a position of weakness; they need something they lack. In contrast, the bond seller is an active agent in a position of relative strength, selling an asset of positive value.

Ukraine is losing ground to Russia, losing morale among the troops and the citizenry, and finds themselves in desperate need of a cash infusion in order to defend themselves. It needs to borrow even more, and its allies seem more hesitant to loan to them. But what if Ukraine had an asset it could sell?

That asset is a unique bond, whose value is calculated based on future cash flows from Russia to Ukraine. Those projected cash flows take the the form of predicted war reparations. That is, the future Ukraine describes in its (hypothetical) “reparations bond prospectus” is one in which the war has ended and international courts award war reparations to Ukraine, on the basis of Putin’s unlawful invasion of a sovereign democracy. Those reparations are future value for Ukraine in the form of a valid future money-claim on Russia. This is a reparations bond.9

The structure of this bond posits a future money relation between Ukraine and Russia: at the war’s conclusion, Russia will owe Ukraine. Ukraine sells that future money claim by issuing a bond in the present. Of course, the buyers of the bond become Ukraine’s creditors, establishing an immediate money relation between Ukraine and its allies – Ukraine owes them. But more than this, Ukraine’s promise to repay is tethered tightly to its future claim on Russia (through Russia’s projected obligation to repay Ukraine for damage caused by the war).

Selling the bond thus immediately forms the second leg of the triangle: Ukraine becomes the debtor of its allies. But just as importantly, it also pencils in the third leg of the triangle by projecting a future in which Russia becomes Ukraine’s debtor. [Bond Issued]

Crucially, the credit/debt relations of this triangle all run in the same direction: the allies owe Russia; Russia owes Ukraine; Ukraine owes the allies. In theory, when the war ends and reparations are decided [War’s End], all the debts cancel out: Russia gives money to Ukraine (for reparations), which gives it to the allies (to pay off the bond), which “gives money” to Russia by unfreezing Russia’s deposit account, thereby freeing up the funds that Russia needs to pay reparations. In other words, and in simplified terms, all these debts cancel out. [Russia Pays]

But what if, as everyone expects, Putin refuses to pay? It doesn’t change the end result at all. Instead, it merely alters the accounting by which we get to that result. If Russia refuses to pay its debt to Ukraine (in the form of reparations imposed by the recognized authority of international courts), then at that moment Ukraine’s allies can say the following: Russia owes Ukraine but refuses to pay; we owe Russia, but will also justly refuse to pay. Instead, we will simply cancel out the debt we owe to Russia, and replace it with a debt we owe to Ukraine.

At that point the triangle leg connecting Russia to Ukraine has been erased, but it has been replaced with a new link between Ukraine and its allies. Ukraine owes them (for the bond) and they owe Ukraine (for the transferred reparations claim). These two debts cancel out, and again we find ourselves with all debts cancelled. [Russia Defaults]

Notice that the magic of issuing the war reparations bond occurs long before the war’s end. At the very moment the bond issue is taken up, the money relation between Russia and Ukraine is brought into existence.10 That money link is posited by the terms of the bond and then congealed by the purchase of the bond: when the allies buy the bond they make a claim not only on Ukraine as their debtor, but also, implicitly, on Russia (as the future debtor to Ukraine, and the ultimate source of future “cash flows”). That counterclaim against Russia creates the conditions of possibility for leveraging Russia’s frozen deposits in a way that can support Ukraine.

Money can never be seized because it is never a locus of positive value. Money is always a relation, a claim by a creditor on a debtor. But this means that money relations can multiply, intersect, and overlap in an infinite variety of ways. Claims can be transferred from one creditor to another. Counterclaims can offset primary claims. The “wizardry” of financial engineering is not really about sophisticated mathematics; it’s about the production of new and varied claims and counterclaims. In the case of the reparations bonds, such engineering can provide a money solution to a dire political problem, but we see it that way only through the lens of money/power.11

Figure 1: The Money/War Triangle

Everyone seems to agree on the $300 billion number as the rough total of Russian deposits held in western banks. There’s much less agreement on the exact distribution of that number, particularly how much is held in the US. Estimates range from as high as $100 billion (source behind paywall) to as low as $5 billion (claimed here, but with no citation). Perhaps the best source splits the difference at $67 billion. Moreover, aside from a screenshot of an excel spreadsheet shared on twitter and reproduced in an FT article right at the start of the war, no one really seems to have seen any actual balance sheets. This shouldn’t shock us: there’s a war going on. And one of the simplest insights of the money/power perspective is that when you look at an institution’s balance sheet (from a bank to a corporation to a household) you also also reveal power structures.

I draw from this piece because the quote below nicely illustrates pervasive intuitions about money that sustain the argument for “seizing Russian assets.” My point is not to pick nits with, or mount a damning critique of, the opinion piece author, who himself is weighing in mainly on matters of international law.

Had the ECBR or the Russian government itself rented safety deposit boxes in foreign banks, then I suppose those foreign banks could seize whatever is in those boxes and sell it off for funds to support Ukraine. On the one hand, this is silly; on the other, it again underlines the basic point.

Ukraine can then spend the money by buying US weapons and in effect “writing a check” on the BoE that the Fed will “cash.” (In reality the BoE will simply zero Ukraine’s deposit account and credit the same amount to the Fed’s deposit account at the BoE.) Alternatively, and more simply, Ukraine could just buy materiel from the UK: the UK sends commodities and marks down what they owe Ukraine.

I can immediately imagine two questions readers might raise about this movie:

Why are Russian banks holding bags of foreign currencies? Answer: bags of money always magically appear in movies, and viewers never seem to care where they come from.

Aren’t all J.J. Abrams movies really bad? Answer: no comment.

In some ways this looks most like my second scenario: as criminals, the central bank notes are, by definition, stolen. As agents of the state, the police then steal them back.

Perhaps there is one other angle to take in the (futile, I think) effort to rescue the concept of seizing bank deposits. This would center on the idea that the deposit itself was previously funded by a transfer to the bank, so it is these earlier funds that one would seize. For example, you deposit your paycheck with Banker Betty over a series of months, and your deposits pile up. Those paycheck deposits are loans you make to Betty and your deposit account is Betty’s liability to you. But say Betty then discovers that you are a mercenary soldier working for a warlord, so she decides to keep the money you loaned her (in the form of your deposited mercenary paychecks). Betty informs you that your account is closed and zeroed out; I’m “seizing” your deposits, she says.

At first glance, this sort of works? But on closer inspection it proves really messed up, both politically and temporally (money, as a claim on future value, always necessarily involves both time and power).

Temporally, the money Betty is supposedly “seizing” is not actually there to seize. That first paycheck came in almost a year ago. Your deposits have been funding loans Betty made quite some time ago to individuals, corporations, and governments. That money is long gone. Sure, Betty can decide not to honor her liability to you as depositor, by refusing to let you withdraw money or write checks on your deposits (you can write them, but they will bounce). But she cannot get any extra money out of you.

And politically, Betty has an even bigger problem: the deposits she plans to keep are blood money. It’s easy to say that you, the mercenary, shouldn’t get to spend that money, but we certainly don’t want the banker spending it. This would just be a new source for banking profits: open accounts for war criminals, take in their deposits, and then close their accounts and keep your funding. Moral hazard indeed.

It goes (almost) without saying that the engineering of the reparations bond is as much or more about law and politics than it is about essential economic relations. But this is no surprise: money is always about all these elements at once. This complex reparations bond only proves necessary because of the political roadblocks standing in the way of giving or loaning money to Ukraine directly. This is another way of getting at those connotative differences between a loan and a bond. In buying a reparations bond, Ukraine’s allies get to loan Ukraine money without it looking as if they are just loaning Ukraine money.

Certain close readers of Marx might be reminded of the general form of value (what Marx labels “form C”), which seems to already contain within itself the money form (“form D”) – as Marx notes, “form D differs not at all from form C” (Cv1, 161).

Thanks to Geoff Ingham for the spur that led me to develop this post. Thanks to Rebecca Brown for rendering Figure 1 in a legible hand.

Can I buy a reparation bond to help? My only comment is to assert that, indeed, there are no good JJ Abrams movies

Why would we need reparations bonds at all? Why can't we start with "Putin isn't going to honour the bonds anyway" and go directly to "we will simply cancel out the debt we owe to Russia, and replace it with a debt we owe to Ukraine"? The West can then honour this debt by paying in weapons or whatever else.