Stablecoins: Reinventing the 19th-Century Banknote

A true innovation for anyone who needs to do crime or evade taxes

Henry Farrell and Dan Davies have an important NYT piece1 out on The Genius Act, which late last week moved forward in the Senate. As they rightly say: the point of this piece of legislation is to legitimate crypto by using stablecoins as a battering ram to “break down the boundary” between crypto and traditional finance.

This is a terrible idea, as Dan and Henry illustrate in myriad ways. I’m not going to repeat their very good arguments, nor do I want to replicate my own constant theme that the raison d’être of tether (the most prominent and dominant stable coin) is to help individuals and groups engage in criminal activity. Instead, I want to draw as clear and high-resolution a picture of the actual financial object, the stablecoin, as I possibly can.

Much of the crypto universe can be explained by two principles: crypto bros are constantly making shit up about how new and revolutionary crypto is, while spending most of their time reinventing extremely old elements of traditional finance. In his columns over the past few years, Matt Levine has drafted an entire book (a long one) documenting all of these instances. And my go-to explanation for stablecoins is to point out that stablecoin issuers (Tether, Binance, World Liberty Financial) are nothing more than shadow banks: they take deposits, issue their own liabilities in the form of “tokens” and make their money on the difference between the interest they pay (0%) and the interest they earn (greater than 0%).

But as Dan emphasizes in his own substack post, “stablecoins really, really are different.” As I read him, Dan’s claims revolve around stablecoin institutions and the overall regulatory environment. To legitimate Tether, which issues tethers, is both to treat it like a money-market fund issuer, and also to fold it into the same regulatory environment. But every banking institution is connected to every other, and this makes contagion a gigantic risk. As Dan puts it:

if USD stablecoins are in the system, they’re in all of the system. If one of them collapses, or blows up (or even has a major IT outage), people will immediately worry about whichever banks had exposure to the bust stablecoin. Then they will worry about who might have exposure to the banks on that list, and so on.

Up to this point in time, crypto and tradfi have been kept quite separate, which is precisely why the massive collapses in crypto winter had only the most isolated impact on both traditional banking and the overall economy. The Genius Act is a horrible idea because it exposes all of us to the evil madness of the next Sam Bankman-Fried.

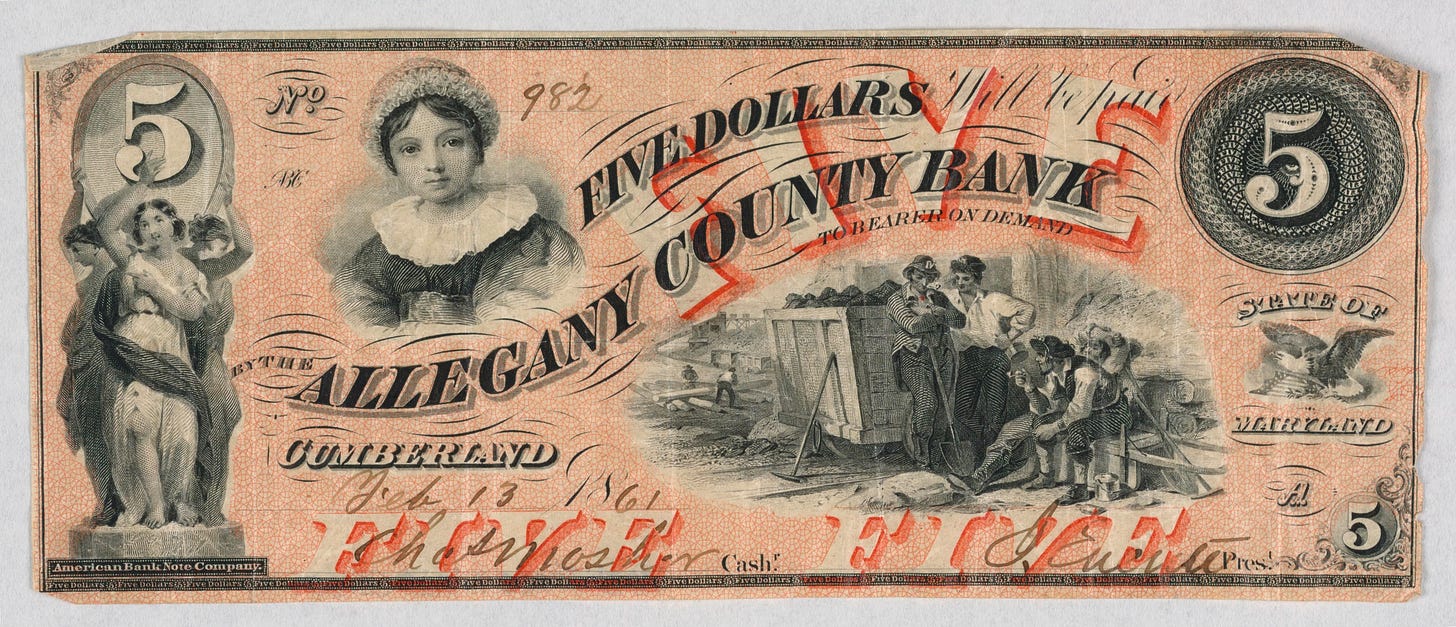

So far, so good. But there is one more, crucial wrinkle. Tether isn’t just a MMF issuer that is harder to trust, because the tether itself has distinctive properties. Indeed, stablecoins are arguably the first and only real financial innovation of the entire “crypto” universe. What, then, is a stablecoin?2 In this post I’ll try to show you why and how it’s a digital version of the nineteenth-century banknote.

Presumably pressed by the NYT editors to avoid all technical discussions, Henry and Dan offer this working definition of stablecoins: “crypto assets guaranteed by other assets like the U.S. dollar.” I get why they start here, I really do, and I know they know full well how a stablecoin works. But unfortunately this language replicates the confusion that lies at the origins of crypto (in Satoshi’s bitcoin white paper), which is also the common confusion about bank deposits.3 This is the dream that a crypto token can be generated by a computer and immediately have positive value.4

But a stablecoin is not an asset of the issuing institution. Tether can create tethers, but they create them as liabilities of the Tether institution. Thus a stablecoin isn’t really a “crypto asset” at all, and certainly not in the sense that many crypto enthusiasts would like to think of crypto as uniquely capable of generating new value out of clever computer code. The starting point for understanding a stablecoin is still the model of the bank: deposits are loans that customers make to the bank. “Value” only emerges in the swap of IOUs, because when the make creates a deposit account for me (my asset) they also create a loan for them (their asset). When it comes to banking and money there are only ever assets if there are also liabilities. Bank deposits are the liability of the bank, and this is what makes them an asset for depositors – the fact that the bank owes them.

Now, the bank can tell all sorts of stories about why their liabilities are sound, but bank deposits are never guaranteed, because no debt can ever be guaranteed. In the same spirit, bank deposits are never “backed,” because the bank does not and cannot hold onto something of definite, positive value that would guarantee the deposits. When people supposedly deposited gold in the 19th century, banks did not keep it for them in their vaults. When people deposit cash today, banks don’t hold onto it, nor are they able to swap it for something else that is of secure value.

We can never forget that, as an existential matter, the bank must do something more risky with your money than you are doing in depositing it at the bank. Bank deposits are, by definition then, not guaranteed or backed by the bank. Of course, they can be supported by other institutions and by a regulatory framework; that is precisely how banking works today. Silicon Valley Bank didn’t “guarantee” its depositors’ accounts: SVB was unable to pay back all the money because its depositors rushed to withdraw it at the same time (that’s a bank run). But then the FDIC stepped in and gave those depositors new money. As I’ve said many times before, Tether doesn’t have a bank charter and is not regulated, which means they are not supported by the FDIC (nor regulated by the SEC, or FINRA, etc.).

But here comes the twist: Tether is not just a shadow bank because stablecoins really are different in their technical constitution. The difference between tethers and shares of a money-market fund is that tethers circulate freely and do so beyond the confines of the banking system. For me, this is the key to Dan’s point that the sophisticated, regulated banking system is very different from “people emailing each other magic numbers.” In the crypto universe people have been emailing one another magic numbers for a while now, but despite all the hype, most of the time those numbers were not money. Stablecoins change that: they make possible a somewhat decentralized5 digital cash.

Let me spell out the specificity of the stablecoin by way of a series of contrasts:

Stablecoins are unlike decentralized crypto (e.g., bitcoin), because the former function like bank deposits (they are liabilities of the centralized issuer) while the latter are virtual/faux commodities that are the liability of no one.

Stablecoins are unlike real bank money because they are issued by institutions without a bank charter, and therefore operate outside of the regulatory environment that makes a bank a bank.

Stablecoins are unlike shadow bank liabilities (e.g., MMFs) because stablecoins circulate. People pay them directly to their counterparties and outside the purview of the stablecoin issuer.

Since the 2008 bitcoin white paper explicitly thematized this point, people inside and outside the crypto space have wanted to describe crypto as “digital money,” and to suggest this was revolutionary. But as so many patient commentators have explained: digital money has been around for a very long time; everyone who has a bank account has “digital money.”

But there is a key difference between that form of digital money and the form brought into being by stablecoins. When I pay with a check, debit card, or ACH transaction, I authorize my bank to directly transfer funds (i.e., move around numbers in cells in spreadsheets) on my behalf. Each individual transaction I conduct includes the bank at each step. But if I pay with tethers, I merely pass on the claim on the Tether institution, without directly involving Tether itself.

Stablecoins are unique not because they are “digital dollars” but because they are digital banknotes. In the nineteenth century, bank depositors would get actual banknotes: special, printed up objects that specified the debtor (the issuing bank) and the denomination. The holder of such notes could then try to use them for payment, and this would work to the extent that the person they were paying recognized the bank as legitimate and accepted the notes. These notes did, in fact, circulate. This made them not only money (a denominated claim on a debtor), but also cash (the thing that counterparties would recognize as direct payment for goods or the clearing of prior debts).6 But they circulated in limited, local spheres, and they often circulated at less than par.

It is absolutely crucial to remember that stablecoins also circulate in very limited domains as well: right now, as I’ve detailed before, that means that stablecoins circulate in the crypto casino cashier space (the place where you exchange dollars for crypto chips, and vice versa), and they circulate among criminals as a substitute for duffel bags filled with cash. Indeed, it’s this second example that truly draws out the innovation of stablecoins as digital banknotes, because crime has been conducted for a very long time using US Federal Reserve notes as money. Only recently have criminals had the option to use stablecoins, aka digital banknotes. This has also proved very convenient for money laundering, because it’s so easy to swap stablecoins for crypto assets, and back again, with specific exchanges known as “mixers” rising to meet this need.

Thus we may think of the Genius Act as an explicit effort to legalize and normalize these twenty-first-century digital banknotes, which truly are a novel creation. Alas, the only problems that digital banknotes solve are the inconvenience of doing crime with heavy paper money, and the nuisance of having to pay taxes on observable monetary transactions.

And each of them has a great follow-up substack post on the topic as well: here’s Henry, and here’s Dan.

In this post when I say “stablecoin” I mean only the type issued by a centralized exchange or shadow bank, which today seems like the only kind that matters. So-called algorithmic stablecoins, in which one coin is meant to be magically supported by the value of another coin, have already been proven to be impossible. But no one should assume they won’t make a comeback at some point.

Which is also a confusion that keeps the dream of crypto alive to such an extent that when one individual tortures another one for days, the NYT still describes them as a “crypto investor.”

For those inclined to think, “wait, isn’t this exactly what happens in bitcoin mining today: the bitcoin protocol awards the winning miner money?” – I remind those readers that the bitcoin protocol just assigns some specified quantity of the bitcoin “value” variable to the miner’s address, and for many years that quantity of bitcoin was nothing but points in a video game. Only when exchanges appeared – exchanges functioning exactly like banks – did it become possible to swap those bitcoin points for real money, i.e., bank money.

This hedging phrase – “somewhat decentralized” – attempts to split the difference between two untenable positions. On one pole would be acceptance of the crypto hype, assuming that stablecoins are part of the techno-libertarian dream of completely decentralized money. That’s false because Tether (and every other stablecoin issuer) is a centralized institution. Your tether is a claim on the Tether shadow bank, not a decentralized token. Stablecoins may be a functional part of the current techno-libertarian politics, but they are a far cry from the dreams of Satoshi (with bitcoin), or even Hayek (with purely private money). On the other pole would be the rigid insistence that Tether is no different from every other shadow bank (I have fallen prey to this rigidity in the past – mea culpa). This is false because tethers now circulate widely in transactions that do not involve Tether at all, something that cannot be easily said of most other forms of shadow bank money.

I think a lot of confusions arise about “money” because we often conflate it with cash. But, I have argued that “cash” is actually a relative concept, because what counts as cash depends on who you are and where you fall along the hierarchy of money.